Archive for March 7th, 2009

Tulips and Uzis: Travels in Israel

The Negev desert leaves you feeling very clean, its sun-scorched space filled with a light bright enough to bleach your bones. The desert floor is crisscrossed by ancient trails clearly visible from my vantage point on top of the Ramon Ridge. Here, in the Fourth Century BC, Nabatean camel caravans carried perfumes and frankincense and bitumen from the deserts of southern Arabia to the Mediterranean ports. A paved road stretched across the desert from Gaza to Petra in Jordan, the Nabatean capital. Among their gods was the moon deity Hubal, worshipped at the Kaaba in Mecca.

The rocks here teem with ammonite and other fossils. Humans have come and gone in this desert for fifty thousand years. You can see the ruins of a fort high on a promontory, and in the valley there are giant cisterns, their water now an ancient memory. Today the tracks are trod by wild onagers, along with Israeli hikers out for a scorching wilderness experience and the odd SUV packed with camera-toting tourists.

View from Ramon Ridge

Ibex Looking for Company

Israel is mostly the Negev. As you travel the narrowing triangle from Bersheeva — where Abraham, a mercenary for the King of Sodom, came and pitched his tent — to Eilat, the glittering resort on the Dead Sea, you come across mile upon mile of barbed wire, enclosing military camps, prisons, and firing ranges. There are army trucks, even tanks, on the road, and F-16’s screaming across the desert sky – all part of the modern Israeli state created by grit and determination and the help of our American tax dollars.

On the road to Bersheeva, you come across clusters of Bedouin shanties constructed out of rocks, cardboard, and garbage bags. A little boy runs after a pair of straggly goats, slapping them with his stick; a woman in a dusty scarf and flowing dress sits astride a donkey. These nomads once eked out a living navigating across the desert, guided by the sun and stars and the stories of their ancestors. Today they have been forced to yield their way of life to the military camps. Like other nomads, they are disparaged as thieves – car thieves, according to my Israeli driver Yossi. I did see a battered sedan at one of these camps, with an old man hard at work on the engine. As he worked there all alone with the garbage bags flapping in the wind, it was obvious he was just repairing his vehicle.

Yossi waves his hands a lot while driving. He gives me a breakdown of Jewish dietary restrictions. Live food is exemplified by milk from kosher animals. Dead food includes food from cloven-footed, cud-chewing animals. Fish must have scales and fins, so that shark and shrimp are forbidden, with a few shellfish falling in between. Other creatures aren’t kosher, especially the pig, which Islam also abhors. Live food and dead food cannot be mixed – they create an imbalance in the system.

I tell him that in India we have all kinds of food sects, from vegetarian Jains who stay away from tubers, to worshippers of Kali who were rumored to feed on corpses. He raises an eyebrow. I add that there are also cosmopolitan couples who snack on foie gras in their Bombay flats. Our chatter about food habits and preferences makes me wonder about food in the ancient world, with the traditional Chinese as well as the Indian Ayurvedic systems being based on a theory of humors similar to that of Hippocrates and Galen.

Bersheeva is very much a frontier town, with a large and dusty bus-station and grimy shops run by Russian money changers. Bersheeva is only 50 miles from Jerusalem, and it is the first stop for tourists heading south into the desert. As I watch disheveled backpackers and haggard Palestinians getting on to buses, the microscopic scale of the country becomes clear. Bethlehem is just 7 miles from Jerusalem. The northernmost city, Haifa, is just 140 miles from Eilat, the southernmost. How could such a tiny country be such a powder-keg for world conflict?

Nevatim

From Bersheeva I take the bus to Nevatim, to visit a settlement of Indian Jews from Cochin. As the bus stirs up clouds of dust along the sides of the road, I nibble on cool sandwiches that have come wrapped in moist cloth napkins. My hosts of the previous night have packed me a delicious lunch, along with fruits and water for the journey. As my teeth sink into grainy brown bread and fresh lettuce, soft cheese, and tomatoes, I am grateful to them, and to most of the Jews I have encountered along the way. They are a people of unmistakable warmth to their friends, lively and disputatious, the women languid and dark-haired, moving with an easy Mediterranean grace.

As for their enemies, it’s back to Yahweh, the god of the Old Testament breathing down ruin and devastation. Long before that, according to Karen Armstrong there was El, the Canaanite High God, and Al-Lah, the high god of the ancient Arabic pantheon, in the days when the people living here were still poly-theistic. I mull over these ancient superstitions as I pass the groves where Abraham might have camped. Gnarled fig trees, olive groves, a canyon here, a rugged mound of rocks there, all ancient places seared by the sun.

The Jews of India are a multifarious tribe. When lighter-skinned European and Middle Eastern Jewish settlers arrived in Kerala in the eighteenth century, they quickly adopted a caste system, with the White Jews being distinguished from the ancient natives, the Black Jews, both of which communities lorded it over the Meshuhrarim, who were freed slaves. In addition to the Cochinis, there are the ancient Bene Israel from the Konkan coast (who had their own color bar), the Baghdadis of Bombay, dating back to the 1800s, as well as several more recent twentieth-century converts from Christianity. The latter include the Bene Menashe, consisting of Kuki and Mizo formerly headhunting tribes from northeastern India who had been — astonishingly — accepted by Israel in 2005 as being truly of the ilk, leading to protests by Indian evangelical churches about mass conversions to Judaism. In contrast, a band of self-declared Telegu Jews, the Bene Ephraim, have been ignored by the Israeli rabbinical authorities. Given this diversity just among Indian Jews, perhaps the term ‘Jew’ is today as uninformative as to particulars as the term ‘Latino’. Or ‘Indian’, for that matter.

The Nevatim Jews, like many others arriving in Israel, were immediately plunked down in the desert with the goal of making the arid land “bloom”. And, like others far from home, their first impulse was to build a place of worship. Rachel, a helpful young lady in Nevatim, explains that their synagogue is an exact replica of the one in Cochin, from where they had carried away various ritual objects.

Rachel

Rachel shows me copies of two engraved plates from the Eighth Century, which stated that the local satrap, the Chera ruler King Bhaskara Ravivarman II, was granting dominion over the Jews of Malabar to one Joseph Rabban, giving him the right to various lands, tolls, and a palanquin, among other items. Next to them, on a wall plaque, it said a man without a past had no present and no future.

“We had eight synagogues in Cochin,” Rachel says. “We had coconut palms, banana and papaya trees, beautiful beaches. Here there was nothing but desert and terrible dry heat. With no servants, nobody to help us.”

“It must have been hard.”

She nods. “My mother had never worked, she had only kept house, with the help of servants. Now she had to become a manual laborer, digging and planting. She nearly broke her back.”

“How did you manage to prosper?” There are plenty of trees and shrubs, date palms, nicely paved roads, a park – it seemed like a pleasant place to live.

“I’ll show you,” Rachel says. She picks up her Uzi, and takes me for a tour of the settlement.

Soon we are inside a cool, air-conditioned building. Around me is a buzzing bloom of bright, bulbous flowers, in every color under the sun.

“Tulips,” she explains. “For the world market. My father and his relatives decided early on to get into export.”

It is a story of enterprise and determination, the same combination that had made them masters of the spice trade in Cochin.

“Don’t you all miss Kerala?”

“How can we forget it?”

It turns out she is a fan of all things Indian, including Malayalam movies and cricket. She has all the blind enthusiasm expatriates have for the new India, and she would love it if India became a superpower.

“I admire everything India has accomplished,” she says. “And I love Mumbai.”

I scrutinize her Uzi, its ugly black contours leaning quietly against her gorgeous hips. She has completed her military service, and is very familiar with the use of weapons. It seems so incongruous to imagine this charming young woman as a sniper, firing at Palestinians for sport or self-defense.

Rachel introduces me to some of her friends, all of them well-proportioned and in the very flush of youth. They seem like young people everywhere, baring their bellies and wearing tight jeans, and giggling and talking very fast, except that they all carry Uzis.

“In case of terrorist attack”, a girl says. There is an ever-present danger.

I try explaining that many other countries have experienced terrorism, independence movements, and the like, but we didn’t walk around sporting submachine guns, but they merely shake their heads. Obviously, I am not a Jew, and would never understand.

Bethlehem

On the way to Jerusalem, I stop at a dagger shop in Bethlehem, close to the Church of the Nativity, where I run into four young Palestinian Christians. They do the one thing that people in many parts of the East do when greeting an Indian – they wiggle their hips, pretending they’re dancing in a Bollywood movie. We end up lunching together. We enter a huge, deserted restaurant. As we nibble on olives, I learn that the owner is away in prison; he’s a member of the PLO. Have I been to the camps, they ask, thinking I’m a journalist. It will really wake me up to see what is going on. No, I say, I’m here on holiday.

The waiter serves us a gigantic fish, grilled to perfection. We tear at it with our fingers, scattering bones all over the tablecloth. Meanwhile, we talk about the folly of war, the terror of occupation, and the plight of Christians. I secretly fondle my dagger, which has large glass pieces for what should be semi-precious stones. We drink an enormous quantity of beer.

Masada and the Dead Sea

The Roman-build fortress of Masada is a place of ritual pilgrimage, commemorating the deaths of 960 Jewish rebel holdouts in the face of a siege by the Romans. Rather than being taken alive, the rebels committed suicide, after first killing their wives and children. It is sad that this tragic episode should be taken as a symbol of the ideals of the Jewish state. An archaeologist from Ben-Gurion University is at hand, talking about recent discoveries about life during the siege. The view from the hilltop is breathtaking, including as it does the remains of the victorious Roman camp, its magnificent outlines preserved permanently in the desert.

Masada View

Masada Sign

Masada: Roman Camp

From Masada I travel down to the Dead Sea for a ritual immersion in its saline waters. It feels hot and strangely uncomfortable, and afterwards, my skin tingles. I have to skip deftly across the burning sand to the shower rooms. The heat is intense, and as the vendors nearby call out to me, their voices floating away in the warm breeze, I am suddenly glad, at home in Asia.

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is an atmospheric walled city with four distinct quarters, Christian, Armenian, Jewish, and Moslem. It is a city that moves at a slow place; after centuries of almost continuous strife, she can afford to take her time.

Jerusalem

Jerusalem Signs

I stroll down the Via Dolorosa past the Church of Flagellation, where it joins the street called the Mujahidin. There are as many churches here, it seems, as in the Christian quarter. The Moslem quarter has more butcher shops. I pass many Americans, some of them in orthodox garb. On the hills above, I can see fine mansions being erected, bulldozers crunching up what remains of ancient homes. I am reminded of a fragment of a poem by Yehuda Amichai:

Laundry hanging in the late afternoon sunlight:

The white sheet of a woman who is my enemy,

The towel of a man who is my enemy,

To wipe off the sweat of his brow.

Relics

At the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, they are giving a guided tour, explaining to Poles and Italians about where Jesus is. All the business about relics, Jesus’ shroud, Buddha’s teeth, not to mention the stoning of devils, the feigned drinking of blood – quite fascinating, but aren’t we supposed to be past all that silliness? But isn’t this what humans are really like — still throbbing with ancient feelings?

Dome of the Rock

The Protectors

The Dome of the Rock is under repair, as it must have been so many times since it was first built in 691 AD over the site of the temple of King Solomon. As in India, there are nutcases who want to rebuild ancient temples that have been overrun by mosques. They seem to have forgotten the words of Rabbi Hillel, who formulated the Golden Rule of Judaism: Do not do unto others as you would not have done unto you.

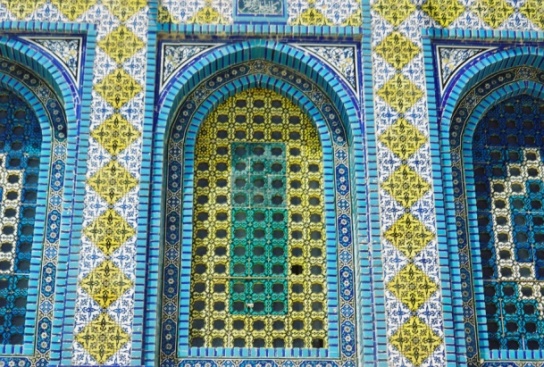

Windows at the Dome of the Rock

Calligraphy

More Calligraphy

My Arab guide stops short at the Wailing Wall, part of Herod’s Temple. He spits, cursing the Jews. The tour stops here – if I want to touch the Wall, I must go with a Jewish guide. After a bit of bargaining about his fee, I leave him, passing an Orthodox Jew shouting agitatedly in the language known as Brooklynish into his mobile phone, in between stealthy puffs of a cigarette. At the Wall, I am touched by the sight of people tucking in prayers.

The Wailing Wall

Hungry Soldiers

Golden Arches

Israel’s conflict is everyone’s; I am an outsider, but as opinionated as the ones forced to live in this mess. My anger turns to the Anglos – perhaps, instead of taxing us American taxpayers, we should really turn back the clock and ask for reparations from the British? After all, it is they who have sown the seeds of all this ugliness, and not just here, we Indians and Pakistanis are also beneficiaries of their scheming. But it’s rude to point fingers, and I, still bearing vestiges of anglophilia, am writing in this language only because of them.

At other times, seeing the hardworking falafel vendors, the ice-cream carts and baristas and the like whom I patronize, I can’t help but weep for these talented people, praying for them to be allowed to go along with their business without troubling anyone. That is what all of us want, but the settlements continue and the occupation goes on and the F-16’s keep screaming over the desert, and the so-called terrorism doesn’t stop.

A Quiet Observer

On my last day in Jerusalem, I pause for a leisurely breakfast in the Germany colony. There are old stone bungalows here, and I can hear the delightful sounds of people, mainly women, going about their chores, getting their houses ready. Everything is clean, spacious, and relaxed. I order hot bages, which I eat with cheese, Arab cheese called tabne. Add to that capsicum, cucumber, tomato, and olives.

In the cafés around me, young men with their sunglasses raised are casually meeting for a coffee, swinging a few deals over their mobiles. Perhaps later they will saunter down to the office for a bit – ça va aller, why to exert too much! Life is relaxed, until the next attack. A dazzling beauty sits down next to me, tucking her uzi safely between her knees. Earlier, in a cool house built around a courtyard, Nurit, in her silver anklets, had spoken of her hiking adventures all over India. It was what she did after military service, spending her money seeing the world. She loved India most of all, she said, fingering my necklace. She had taught me a few handy words — bevakasha for please, sherootim for the bathroom to wash up in, chaver for the friend I will remain.

I depart for the airport before dawn, as I always seem to be doing, whether in Barcelona, Colombo, Paris, or Venice, the hour when cities are at their cleanest, when the early risers prepare for yet another day. The shuttle bus has one other group, a Greek family. A mother, her daughter and grandson son from the island of Rhodes in the Aegean, are on their way back after saying prayers for their departed paterfamilias. The old lady has white hair, tucked into a dark bonnet, and the daughter has a large beauty spot on her cheek. They finger their rosaries, smile briefly at me, and then return to their devotions.

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( 1 so far )